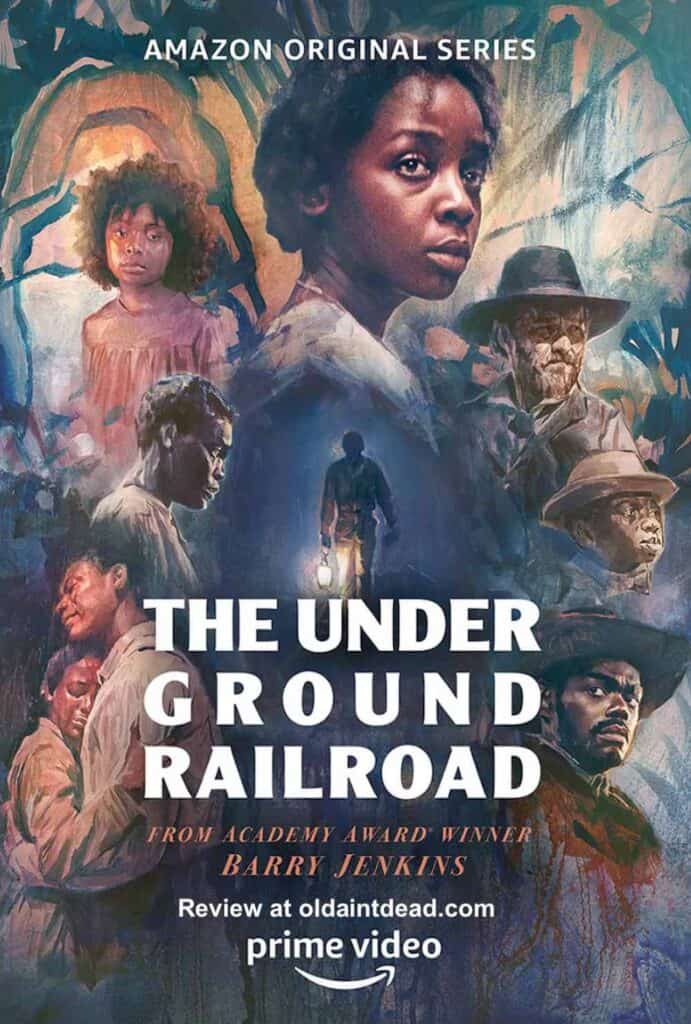

The Underground Railroad is a 10 part series on Prime Video. It was created and directed by Barry Jenkins, based on The Underground Railroad: A Novel* by Colson Whitehead. It’s the story of a runaway slave and the man who pursued her. It was both brutal and beautiful.

I found The Underground Railroad to be a mix of styles. The series was set in the 1840s. There were fantasy elements – for example, the railroad was a real train and was actually under the ground. There were ideas and events shoehorned in from the wrong time period – for example, Black women being sterilized by a group of “helpful” white people. There were lengthy nightmare sequences and frequent stops in the action as everyone in a scene stood frozen in a tableau.

The pacing was also a mixed bag. Sometimes agonizingly slow while other times the story proceeded briskly. The first episode, showing life on the plantation, was so brutal it was almost traumatic to watch.

On the other hand, almost every above ground frame in the film was a work of art. Many scenes were under the ground or in a dark house lit by one candle. However, the outdoor scenes used light and sun in brilliant ways. There were frequent gorgeous wide looks at the areas where the main character found herself.

Cora (Thuso Mbedu) was the main character. Left motherless at an early age, she lived on a cotton plantation in Georgia. She witnessed unforgettable horrors all her life and moved with heavy melancholy through most of the film. She didn’t express her pain aloud until very late in the series, but you could see it in her eyes, her body.

Toward the end of the series we took a trip back to Cora’s childhood to find out where her mother, Mabel (Sheila Atim), went.

As Cora grew up, a man named Caesar (Aaron Pierre) loved her and convinced her to run using the railroad. They fled to a kind of fairy tale town in South Carolina where Black refugees were treated with a charade of respect and dignity, but were exploited, sterilized, and often murdered.

Although the story told in this series wasn’t always what happened or when it happened, it all happened somehow and somewhere. It’s still happening today.

Cora ran alone from South Carolina and ended up at the end of a rail line in North Carolina. There Martin (Damon Herriman) and Ethel (Lily Rabe) hid her in an attic like Anne Frank. There was another younger child hiding there, too, Grace (Mychal-Bella Bowman). Outside their secret attic space was a town based on religious insanity worthy of a Margaret Atwood dystopia. Religion is a tool used to subjugate and justify, not to enlighten.

The slave catcher chasing Cora, Ridgeway (Joel Edgerton), caught up with her in North Carolina. He and his helper, a free Black child named Homer (Chase Dillon), took her and another runaway and headed west across Tennessee. Tennessee was on fire and they traveled for days through a smoldering forest.

Ridgeway got almost as much attention in the story as Cora. She was the ferocious and brave woman fighting for her life. He was the white supremacist determined to dominate and exploit her. We saw into Ridgeway’s upbringing and his relationship with his father.

An effective technique in the series was to repeat the same scene or dialog in different ways. Ridgeway was used to explain the ideas of manifest destiny and white supremacy several times, with less and less effectiveness each time. Ridgeway’s scenes were often accompanied by the sound of a ticking clock, as if the time of slavery or the notion of racial superiority was running out.

After several attempts, Cora got away from Ridgeway again. She ended up in Indiana.

Royal (William Jackson Harper) was the underground railroad conductor who took Cora to Indiana. He took her to a Black owned, community-run farm and winery. The place was like paradise and the people were prospering. Prosperous Black folks became a problem for the white townsfolk. And Ridgeway was still after her.

Some of the speeches and comments made by the people on the farm in Indiana were quotable summations of the slave experience and the behavior of white oppressors.

In Indiana, Cora had time and safety to try to deal with some of her losses and demons. But there were more losses and more running ahead. At the end of the series, we still aren’t sure if Cora will make it to safety somewhere. How could such a story end on a happy note when African Americans still carry the pain of the past and the present with them every day?

I found the series uneven. I wanted more scenes helping us know the very quiet Cora and fewer scenes painting Ridgeway as sympathetic. I wanted more physical illumination in the dark scenes so I could at least guess at what people were doing. But, overall, the series has a powerful effect. It rings emotionally true. I’m sure it will be highly praised and rewarded.

Here’s a preview.

Have you seen this one? Do you plan to watch it?

*The Amazon book link is an affiliate link.

Discover more from Old Ain't Dead

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The end of the real network known as the Underground Railroad was in Canada. The trials and tribulations were exciting and harrowing enough without inventing fantasies.

It’s too bad they had to stoop to such devices. It sounds insulting to me that they felt they needed to do that – a further distortion of history. Like we need more of that.

Disappointing.

Did you watch “Harriet?” https://oldaintdead.com/harriet-puts-harriet-tubman-in-heroic-terms/

Hi,

I agree with John Newell. What happened to enslaved people in this country is an undertold story. When I grew up, that era of American history was totally left out of the history books from the perspective of the enslaved people. The fantasy sequences and the other techniques described in this blog to tell the story of an enslaved person seems, on the face of it, to trivialize the horror and degradation of the lived experience, the actual reality.

I’m willing to allow a writer or a production dramatic license to tell a story, but not here, not ths story. So, I’ll pass. I will, however, add the Harriet Tubman drama to my watch list.